Book Review: Sottsass

Author: Philippe Thomé Publisher: Phaidon Date: 2014 Reviewed by: Adam Richardson

Philippe Thomé's enormous, encyclopedic homage to the great designer, simply called Ettore Sottsass, is a stunning piece of work that belongs on the bookshelf of anyone even remotely interested in industrial design, architecture, furniture design, or the creative process. Bizarrely described on Amazon by the publisher, Phaidon, as a "glimpse into the archive", this tome is anything but a glimpse. It is a full-on walk through of every moment of a long, incredibly prolific and creative life. Almost every one of its 450+ pages is filled with sketches, photographs of products and buildings, and photos of - and by - Sottsass himself. Unfortunately the terrible images on Amazon also don't give any indication of the riches inside - I hope this review will convince you that this expensive book is well worth the investment.

(Click any image to expand.)

Opening the magnetic clasp of the minty-green cover reveals a chronological history broken into thematic vignettes by colored dividers. The titles of these give a sense of the breadth of Sottsass' incredible output: architecture, ceramics, industrial design, furniture, graphic design, painting, photography... Like most Italian designers of his generation, Sottsass was trained as an architect, but in Italy that was a more general term that gave one license to work in many areas of physical production, not just buildings. "The difference between architecture and painting is only a technical one" he said. And Sottsass took that license about as far as could be imagined, with probably Charles and Ray Eames being the only other designers who could match his breadth (as well as humanistic touch and experimentation with new technologies and production methods).

Ettore Sottsass was born in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1917, and grew up in the Dolomites area of Italy, which he credits to imbuing in him a fascination with the sensual - colors, textures, shapes, sounds, light. He started drawing and sculpting at an early age, and also took thousands of photographs as a teenager. He continued to photograph while serving at the front of World War II, taking pictures of his army comrades and the local people, and several pages of the book are dedicated to his quite lovely images.

From there the book traces his rapidly evolving architecture and design work, in which he sought to meld the imperatives of mass production and standardized products with the ancient forms and materials that humans had employed for millenia. At the same time, Italy was having to survive on a shattered economy and minimal resources, and needed to find ways to transition from a largely rural and craft-based approach to manufacture. Sottsass' scrappiness at finding paying - if not satisfying - work during this difficult period is vividly captured. "We would work through the night in order to finish the stands for a vermouth advertisement," he recalled, "to earn a few lire while consumed by deep boredom."

Both the text and the illustrations throughout the book are well-executed. I often find that reading texts about design that originated in Italian can be laborious (for example, almost anything translated from Andrea Branzi's writing). But here the English is clear, crisp and easy to follow.

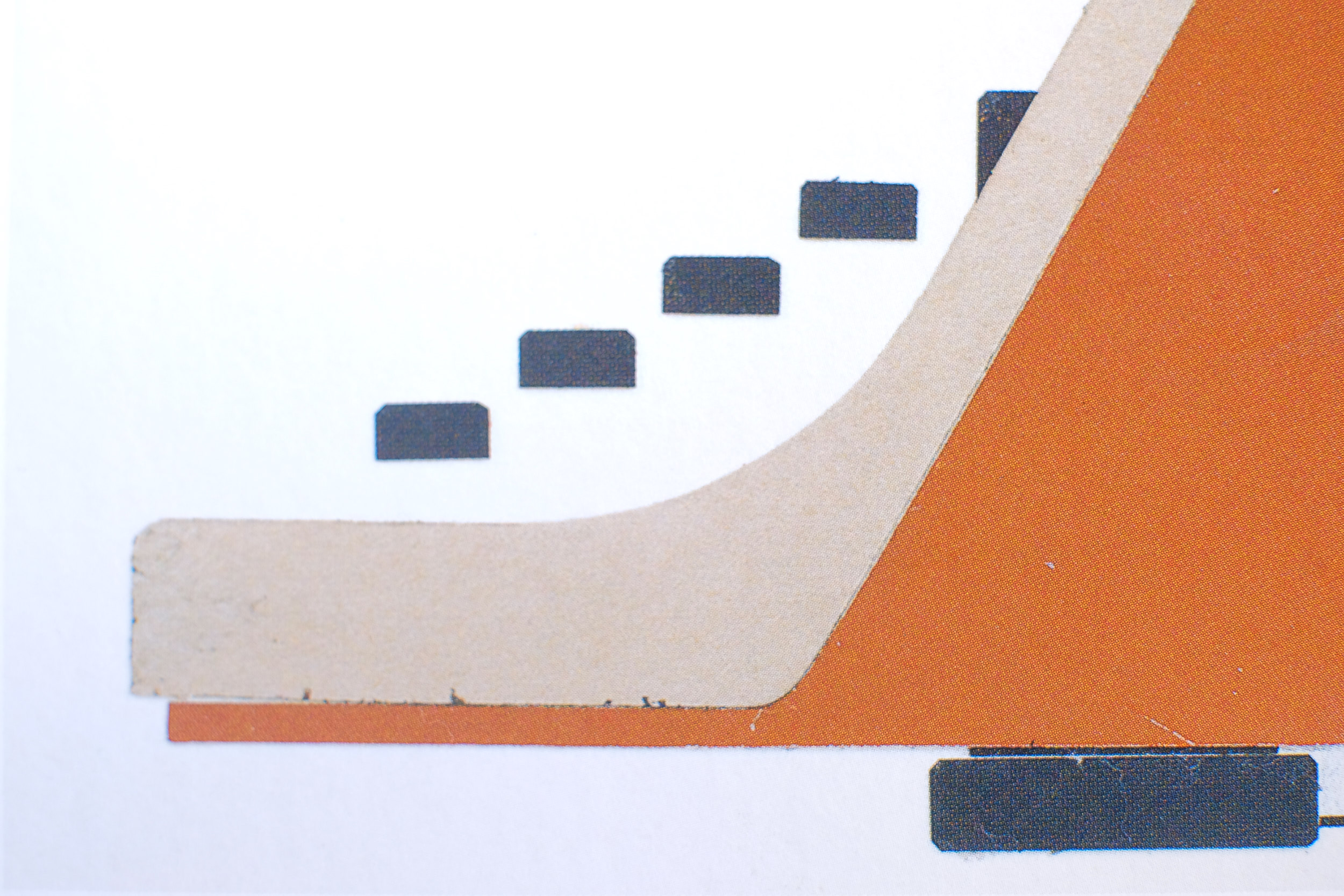

The book showcases dozens of his drawings for buildings and smaller pieces, carefully documented and presented. I particularly liked the small inserts of vellum-type paper that are interspersed throughout, here showing ideas for his famous ceramic ziggurats:

“There’s never been enough said about how ceramics were his testing ground for experimenting with colour and material... For Ettore, ceramics - but also the design of the vases and objects that weren’t strictly functional - were his artistic laboratory, the place where he could experiment, make mistakes, invent, try, fail and try again, transform...in total freedom.”

Olivetti Collaboration

“In contrast to the technology’s mystique, Sottsass proffered a vision based on the people who used and interacted with these new machines, while giving the objects/machines themselves a highly-stylized image: human in scale and vaguely reflecting our traits, even though they spoke a completely autonomous language... [He] assimilated the machines into a landscape scaled to the actions, activities and movements of the operators who worked in symbiosis with them.”

In the 50's, Sottsass' practice focused on architecture, interior architecture and exhibit design, but he continued with his other disciplines as well, such as furniture and ceramics. In the 1960's, he transitioned largely to industrial design, in particular his famous work for Olivetti - arguably the Apple of its day with its blend of technological inventiveness and appreciation of liberal arts and design.

Sottsass started collaborating with Olivetti in 1958, but stayed located in Milan rather than moving to Olivetti's HQ in Turin. He observed, "I was guaranteed a maximum of professional freedom (by that I mean a maximum of cultural flexibility) while guaranteeing the company maximum control over the work done." (A very different arrangement, it is noted, than his contemporary Dieter Rams, who was "embedded" in Braun, and one which became common in Italian design practice, such as for example Richard Sapper's relationship with IBM.)

The first major product to emerge out of this collaboration was 1959's Elea 9003 mainframe computer. Even at this earliest stage of everyday people coming into contact with computers, Sottsass took a humanistic stance, what today we would call user-centered. Francesca Picchi writes in an essay in the book:

His humanistic and systems-level thinking for Olivetti continued to evolve. The Tekne 3 typewriter was envisioned as a small sculpture - but one that would fit comfortably with many other identical ones in an office "like a slice of salami, constituting part of an overall design." The Praxis 48 typewriter in sober gray and bright green key-caps (which we have featured) Sottsass described as "kind of an inside joke: it aims to be a bit funny, joyous but also precious. It engenders a way of looking at mechanics as if you were looking at a toy rather than a real machine: it aims to be an object we are happy to look at, one we approach without fear and without thinking "I must get to work".

It was during this period that Sottsass also became more overtly politically radical, hanging out with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Ezra Pound. The Pop-influenced Olivetti Valentine typewriter was done in this period (1969), and eventually his affinity for counter-cultural ideas of the Beats led in part to his work on the Memphis project.

Memphis

Memphis was formed by Sottsass and several other designers on December 11, 1980, while Bob Dylan's Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again record played in the background, with the needle stuck and repeating the line "Memphis Blues Again". Thus a new movement seeking to break out of design conventions was named after the ancient capital of Egypt and of Elvis Presley's home town.

Even today, Memphis' work from the early 80's has the ability to shock. But Sottsass was careful to say they were not trying to be aggressive in their intent at upsetting conventional thinking. At this point Sottsass was in his late 60's, yet continued to push his thinking in new ways, exploring new aesthetics and ideas, all the while staying true to his foundational principles of sensuousness, humanism, and respect for the historic lineage of culture.

Sottsass died at age 90 in 2007, and Thomé and Phaidon have put together a tribute that does true justice to the man, his ideas, and his work.